Extract, Excavate, Create

Spring 23

Type: Studio

Status: Done, Unbuilt

Location: Ashokan Reservoir, Ulster County, NY

Status: Done, Unbuilt

Location: Ashokan Reservoir, Ulster County, NY

Located 73 miles north from New York City, Ashokan Reservoir supplies constant freshwater to New York City. Ashokan Reservoir is one of six reservoirs owned by New York City in the Catskills/ Delaware watershed system which also includes: Cannonsville, Pepacton, Neversink, Roundout, and Schoharie. The Catskills/ Delaware watershed covers 1597 square miles of upstate New York. Additionally, New York City also owns the area that covers the Croton watershed (375 square miles)[1].

Today the Catskills/ Delaware watershed provides ninety percent of drinking water to the 8.46 million residents of New York City. Through water, the residents of New York City are physically linked to the community of Ulster County. However, this is a relationship of imbalanced extraction. Starting from the construction of the first reservoir in the Catskills (Ashokan) a dispute over resources was already in place. Before water, the land on which to construct the reservoir was the matter in question. After land, the resources including the physical material and labor were in question. The creation of the reservoir is bound to a multitude of extractions of the natural resources around Ulster county, specifically the stone surrounding the reservoir. Furthermore, the construction of the reservoir requires excavation not only on the site of the Ashokan but also the site where the resources are extracted.

This project is a reaction to the extensive claiming of resources in creation of the reservoir, the impacts socially and environmentally, and reparations for the community surrounding the reservoir.

LAND ACQUIREMENT / EXCAVATE

To understand how New York City was able to extract so extensively it is important to look at how the land was acquired in the first place. Through the use of eminent domain, New York City acquired the land. The decision to choose the particular site began when the city made a claim that the “Esopus Valley was sparsely populated, that its hillsides were well forested” which was untrue in many cases. The area was a thriving agricultural hub with an increasing tourism industry and a substantial railroad network [2]. The decision to pick the area was met with immediate pushback from the local community. Judge Alphonso Clearwater represented the interest of the towns affected at a public hearing however they stood no chance against the power of New York City. Underneath the reservoir today, there were thriving communities such as Brown’s Station, Olive City, Broadhead’s bridge, and Ashton. Other towns such as West Hurley, Shokan, West Shokan, and Boiceville were relocated[3] . For example, the hamlet of Bishop Falls which is located at the deepest of the reservoir today (190 feet) was doomed for extinction. The Bishop family had built generations of farming roots and also ran a boarding house. By the start of the reservoir construction in 1908, the Bishop family put up an auction sale notice offering “boarding house furniture, farming implements, etc.”. In a settlement with New York City, the family was paid $17,746.53 for their family land of 106 acres. Later, the family went against the City again for the boarding house and managed $2000 out of it[4].

The people affected from the construction of the reservoir were not only uprooted from their land which often were built by their family many generations prior, they were also excavated to no trace. Oftentimes, during disputes between affected residents and the city for the price of their acquired land, the price is beyond monetary value. Many were forced to accept the value given by the city with no resources to fight back, and if they did, their valuations would be paid in half[5].

RESOURCE ACQUIREMENT/ EXTRACT

On the other hand, the contract to construct the Ashokan reservoir went to a joint bid between MacArthur Bros. and Winston & Co. for the lowest bid of $12,669,775[6]. They soon began working on the construction of the reservoir. In order to manage ease during construction, several new and temporary infrastructures were built. Temporary railroads were amongst the most important as it was the main method of transportation for both people and goods on the construction site. The railroads connect the labor camps, materials, and to the reservoir. The construction of the reservoir required a grand gesture of mobilization from all aspects such as acquiring the laborers from foreign countries, large stones from surrounding quarries, and transporting everything back to the site of the reservoir.

As seen on the contractors map on the reservoir site shows an extensive network of infrastructure. The reservoir was mainly constructed out of stone from the reservoir and its surrounding, limestone concrete likely acquired from its neighboring town Rosendale, and some portland cement. The contractor’s map zooms into the southern tip of the reservoir surrounding the Olive

Bridge dam. It points at several quarries, borrow pits, and the stone crushers [4]. To the left of the Olive Bridge dam is the Yale quarry on Acorn Hill where most of the stones on the reservoir came from. The work at the quarry was conducted under the direction of the Board of Water Supply, City of New York, Mr. J. Waldo Smith, chief engineer, and the contractors were MacArthur Bros. and Winston & Co [7]. The quarry is 1200 feet long and 30 to 40 feet high. A double tract spur from the contractor’s railroad parallel the quarry face, and a row of 10 guy derricks served for the five yard steel skips from the quarry to the car. The cars were placed on one track for loading as they were loaded and taken out by the train. From the quarry, the train carried the stones for three miles to the dam with ten cars in fifteen minutes. The smaller stones went to the stone crushers while the larger stones would be used as cyclopean masonry. By 1911, the Yale quarry was shut down due to sufficient rock supply [8].However, some activities remained until the end of the reservoir construction.

The Yale quarry was an attractive site for stone sourcing due to its geological composition and proximity to the reservoir. Preliminary research was done by the Board of Water Supply, Engineering Department, in search for a local quarry that can provide sufficient quality of rocks. Some other quarries that were considered include Davis quarry, Keator quarry, Beesmer quarry, and Boice quarry. Davis quarry was a little over a mile distant and had strong “reed” but the lowest beds were massive. The Keator quarry was about one and half mile south of the reservoir, however it was underdeveloped and they were uncertain about the stone quality. The Boice quarry on the northern slope of High Point Mt. had excellent rock quality, however due to the distance and the lack of massive stone the quarry was deemed unsuitable. The Beesmer quarry, located two and a half miles south, was the next contestant for the most suitable quarry. The ledge was strong, first class rock, and the extensiveness was probable. Yale quarry on the other hand offered the most out of all the options. First, Yale quarry was the nearest, being only half a mile south of the reservoir. The rocks were massive with cross-bedding tendency and there was evidence of thick bed first class rocks[9]. Throughout the explorations, Yale quarry kept showing promising results. The quarry offered a consistent deposit of bluestone with nearly horizontal strata of varying thickness separated by thin sheets of green shale. The bluestone varied in weight and density showed satisfactory soundness fit for working. The stratification of bluestone varies from 1 inch to 4 feet thick. The bluestone was found outcropping on the face of a bank for 2000 feet long, varying in height from 10 to 40 feet. The excavation at the Yale quarry proved to be successful and furnished all the material for the different classes of concrete and cyclopean masonry at the reservoir[10].

The acquisition of Yale quarry went through several appraisals, one in particular reached Supreme court level. In a publication titled Stone (vol.32) from 1911 highlights the appraisals for several quarries surrounding the reservoir[11]. Yale quarry or Yale farm originally belonged to Mr. and Mrs Yale who sold it to “the syndicate” Jerome H.Buck and James P. Mcgovern, New Yorkers, for a small price[12]. Buck acquired the property for speculative purposes. At the hearing with Commissioners of Appraisals, witnesses produced by the claimants testified that the value of the quarry is higher based on the fact that most of the stones used at the reservoir came from the Yale quarry. The city in advertising the contract for the reservoir gave the rights to the contractors to take the stone from the quarry instead of going to the open market. The city’s witness gave the quarry a value of $7000-$7100, stating that at the time the quarry was acquired there was no market value. The claimant on the other hand gave a value of $960,000 to $1,963,000. After a number of hearings, the settlement was awarded $27,500 which both sides rejected.

The labor intensive process of constructing the Ashokan reservoir required many workers. New immigrants coming from Italy, Ireland, Eastern European, and African-American from the South moved north to begin working at the reservoir. While there were not many records regarding the work at the Yale quarry, some figures showed the dangers and extensive labor needed to acquire the stones. The Engineering Record, Building Record, and Sanitary Engineer (1910) stated that the output of the quarry is limited to demand but can be increased as much as fifty percent if needed. A total of 240 men are employed on two 8 hour shifts. One of them started work at 6 a.m. and the second at 9 a.m.. The work at the quarry was under the guidance of superintendent E.W. Anderson[13]. The work at the quarry mainly consisted of acquiring the stone with the help of explosives and the hard labor of transporting it back to the reservoir site which sits about 2 miles north. For example, the transportation from the quarry requires three groups of twelve men and one foreman to load the skips with the help of the derricks[14]. Unfortunately, the dangerous work at the quarry also resulted in some deaths. A court appeal filed by MacArthur Bros. and Winston & Co. against New York City from 1918 revealed the death of a worker on site. In a settlement against Winston & Co., Germano P. Baccelli from the Italian consul represented Domenico Semproni, the deceased worker. At the time of his death, Semproni earned a weekly wage of $8.65. The settlement stated that Semproni acquired injuries while digging a bay of clay and gravel when a stone fell and hit him which caused a blow that resulted in death on February 27th 1915. The settlement began with $1000 cash. Later, the settlement also mentioned the widow and dependents of Semproni have been receiving cash awards throughout the settlement process. The award amounted to a total of $323.12; for 56 weeks from February 27th 1915 to March 25th 1916 every week the widow and dependents received $11.56. Ernesta Calamari, the widow aged 45, received 30% of the weekly payment ($2.60). The next in line was Semproni’s eldest daughter, Pasqua Semproni, aged 14 who received $0.635. The rest of Semproni’s dependents were Regina, Paolo, Maria, and Giuseppa (aged 12,10,5, and 3). The minor dependents respectively received compensation until the age of 18. At the time, the only living relative residing in the United States was Antonio, Semproni’s eldest son who was also employed by the company. Semproni’s body was shipped to Kingston on a railroad and was buried in a grave in St. Mary’s, Kingston cemetery. The company also paid for the cost of his burial which amounted to $90[15].

CURRENT STATE OF THE SITE: YALE QUARRY

Today, the Yale quarry area is known as the Ashokan quarry trail. The area maintains to be behind the original taking line and a protected area by NYC Department of Environmental Protection recently opened to the public. To access the trail, an entrance with parking is located on the north eastern tip of the site. The trail creates a two mile loop with several artifacts and access to the Ashokan high point. Around 0.3 miles after the entrance hikers encounter the first ruins which are located on a higher ground. The ruin used to house explosives for the quarry. Following a sharp left, comes the highest point of the quarry or the Ashokan high point. On the 0.6 the trail began its loop back on a descending path following the path of the old railroad tracks. The official trail does not include the loading area for the old railroad and remnants of the steel skips. To visit this area, hikers must go off trail towards the northern part of the quarry.

The current state of the quarry shows the extensive stone mining as the bottom of the quarry creates a large concave hole, which is frequently full of water. The trail is also hard to access especially for disabled hikers due to the lack of a clear path. Furthermore, the area seems visibly unkempt as there is a lot of household waste around the site.

CREATE

Last, the most important part of the construction of the reservoir is the creation. The birth of the reservoir is a story that involves massive extraction of resources with unpaid dues for the community and the creators–the thousands of workers of the reservoirs. The reservoir reveals our greed towards resources including the laborers that has brought us to the point of endangerment in the forms of environmental damage and social inequalities. The grim history of excavation and extraction of the reservoir should serve as a reminder of injustices during its creation, however the reservoir remains to be an extraordinary human creation. Since the full operation of the reservoir in 1915, the reservoir has provided millions of gallons of water to New York City. The creation of the reservoir serves as an inspiration for the reparations of the community surrounding the reservoir.

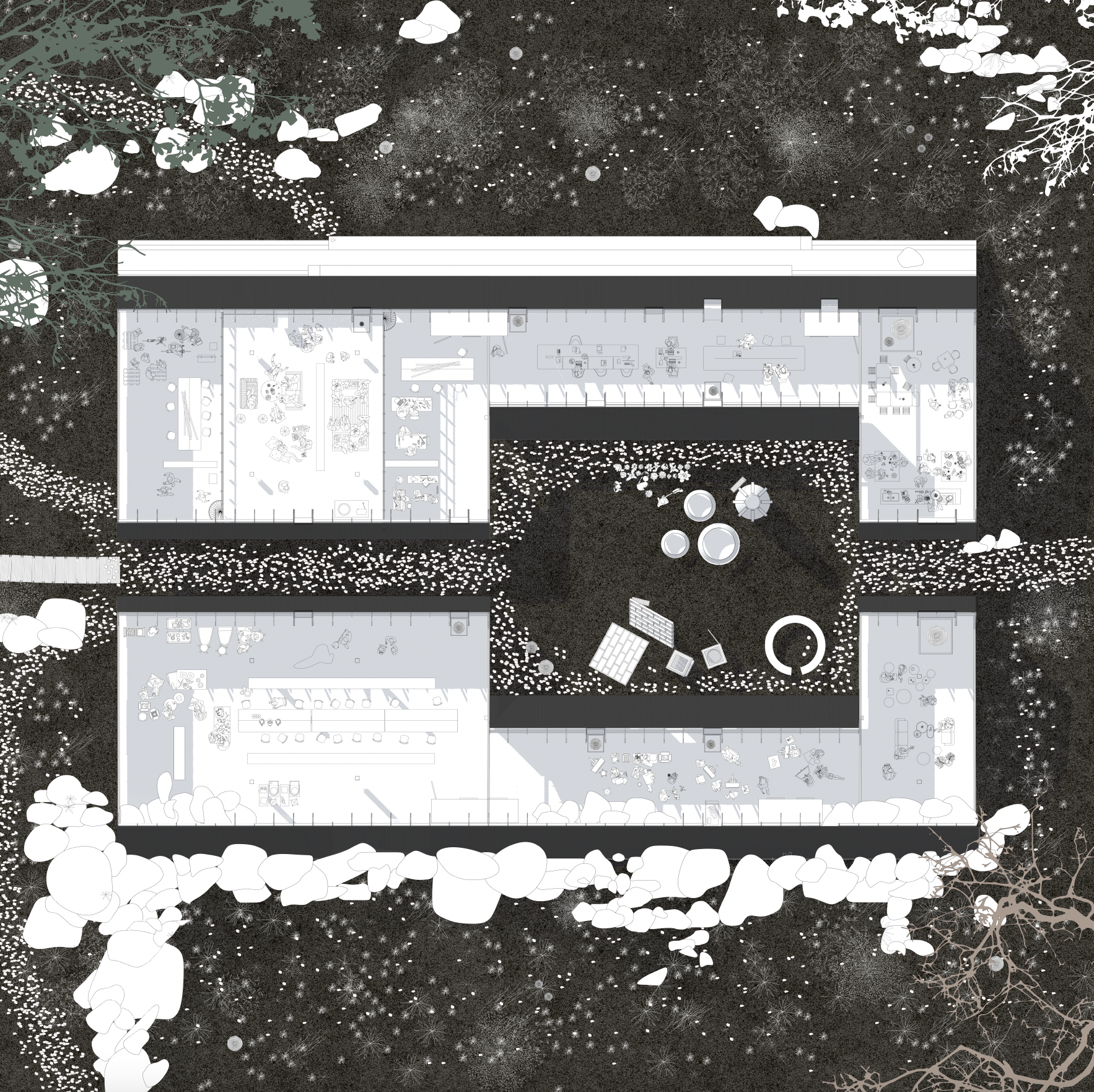

This project seeks to create an alternative architecture school network that integrates with the local community to rethink our relationship with resources through the act of making and waste management. Through the use of local resources and waste the school fortifies the economy of the community. The current state of the surrounding towns of the reservoir lacks access to resources for everyday needs. However, the town itself is rich in resources such as agricultural production. Furthermore, the waste produced adds to the list of resources instead of going to a recycling center outside of the community or a landfill. In this exercise, the community and students are asked to rethink their relationship with material resources. They are asked to rethink a materials life cycle starting from excavation, extraction, and the creation of the product. The language of excavation, extraction, and creation is also repeated throughout the architecture. The materials used for construction also retain accessibility as one of its key points. The toolkits developed include: bins spread throughout the area, storage units, an accessible pathway for the trail, rest points, makerspace compound, gathering area, and a housing compound.

[1] “Croton & Catskill/Delaware Watersheds,” Watershed Agricultural Council, February 7, 2023, https://www.nycwatershed.org/about-us/overview/croton-catskilldelaware-watersheds/.

[2]Stephen M. Silverman and Raphael D. Silver, The Catskills: Its History and How It Changed America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2015), 184.

[3] “Building the Ashokan Reservoir,” Public Water, http://public-water.com/story-of-nyc-water/ashokan-reservoir/.

[4] Silverman and Silver, 186.

[5] Silverman and Silver, 187.

[6] “Lowest Bid Loses Ashokan Contract,” The New York Times, August 27, 1907, pp. 1-14, 1.

[7] The Engineering Record, Building Record and Sanitary Engineer, vol. 61 (New York, NY: McGraw Publishing Co., 1910), 404-405.

[8] Lazarus White, The Catskill Water Supply of New York City ( John Wiley, 1913), 148 & 170.

[9] Charles P Berkey, “Quality of Bluestone Near the Ashokan Dam,” The School of Mines Quarterly, A Journal of Applied Science 29 (1908): pp. 149-158, 153.

[10] The Engineering Record, Building Record and Sanitary Engineer, vol. 6, 404-405.

[11] Stone (United States, Stone Magazine Review Publishing Company, 1911), 367.

[12] New York Supreme Court Appellate Division Third Department (1915).

[13] The Engineering Record, Building Record and Sanitary Engineer, vol. 6, 404-405.

[14] White, 148 & 170.

[15] Court of Appeals 1918 (1917), 941.

This project is a reaction to the extensive claiming of resources in creation of the reservoir, the impacts socially and environmentally, and reparations for the community surrounding the reservoir.

LAND ACQUIREMENT / EXCAVATE

To understand how New York City was able to extract so extensively it is important to look at how the land was acquired in the first place. Through the use of eminent domain, New York City acquired the land. The decision to choose the particular site began when the city made a claim that the “Esopus Valley was sparsely populated, that its hillsides were well forested” which was untrue in many cases. The area was a thriving agricultural hub with an increasing tourism industry and a substantial railroad network [2]. The decision to pick the area was met with immediate pushback from the local community. Judge Alphonso Clearwater represented the interest of the towns affected at a public hearing however they stood no chance against the power of New York City. Underneath the reservoir today, there were thriving communities such as Brown’s Station, Olive City, Broadhead’s bridge, and Ashton. Other towns such as West Hurley, Shokan, West Shokan, and Boiceville were relocated[3] . For example, the hamlet of Bishop Falls which is located at the deepest of the reservoir today (190 feet) was doomed for extinction. The Bishop family had built generations of farming roots and also ran a boarding house. By the start of the reservoir construction in 1908, the Bishop family put up an auction sale notice offering “boarding house furniture, farming implements, etc.”. In a settlement with New York City, the family was paid $17,746.53 for their family land of 106 acres. Later, the family went against the City again for the boarding house and managed $2000 out of it[4].

The people affected from the construction of the reservoir were not only uprooted from their land which often were built by their family many generations prior, they were also excavated to no trace. Oftentimes, during disputes between affected residents and the city for the price of their acquired land, the price is beyond monetary value. Many were forced to accept the value given by the city with no resources to fight back, and if they did, their valuations would be paid in half[5].

RESOURCE ACQUIREMENT/ EXTRACT

On the other hand, the contract to construct the Ashokan reservoir went to a joint bid between MacArthur Bros. and Winston & Co. for the lowest bid of $12,669,775[6]. They soon began working on the construction of the reservoir. In order to manage ease during construction, several new and temporary infrastructures were built. Temporary railroads were amongst the most important as it was the main method of transportation for both people and goods on the construction site. The railroads connect the labor camps, materials, and to the reservoir. The construction of the reservoir required a grand gesture of mobilization from all aspects such as acquiring the laborers from foreign countries, large stones from surrounding quarries, and transporting everything back to the site of the reservoir.

As seen on the contractors map on the reservoir site shows an extensive network of infrastructure. The reservoir was mainly constructed out of stone from the reservoir and its surrounding, limestone concrete likely acquired from its neighboring town Rosendale, and some portland cement. The contractor’s map zooms into the southern tip of the reservoir surrounding the Olive

Bridge dam. It points at several quarries, borrow pits, and the stone crushers [4]. To the left of the Olive Bridge dam is the Yale quarry on Acorn Hill where most of the stones on the reservoir came from. The work at the quarry was conducted under the direction of the Board of Water Supply, City of New York, Mr. J. Waldo Smith, chief engineer, and the contractors were MacArthur Bros. and Winston & Co [7]. The quarry is 1200 feet long and 30 to 40 feet high. A double tract spur from the contractor’s railroad parallel the quarry face, and a row of 10 guy derricks served for the five yard steel skips from the quarry to the car. The cars were placed on one track for loading as they were loaded and taken out by the train. From the quarry, the train carried the stones for three miles to the dam with ten cars in fifteen minutes. The smaller stones went to the stone crushers while the larger stones would be used as cyclopean masonry. By 1911, the Yale quarry was shut down due to sufficient rock supply [8].However, some activities remained until the end of the reservoir construction.

The Yale quarry was an attractive site for stone sourcing due to its geological composition and proximity to the reservoir. Preliminary research was done by the Board of Water Supply, Engineering Department, in search for a local quarry that can provide sufficient quality of rocks. Some other quarries that were considered include Davis quarry, Keator quarry, Beesmer quarry, and Boice quarry. Davis quarry was a little over a mile distant and had strong “reed” but the lowest beds were massive. The Keator quarry was about one and half mile south of the reservoir, however it was underdeveloped and they were uncertain about the stone quality. The Boice quarry on the northern slope of High Point Mt. had excellent rock quality, however due to the distance and the lack of massive stone the quarry was deemed unsuitable. The Beesmer quarry, located two and a half miles south, was the next contestant for the most suitable quarry. The ledge was strong, first class rock, and the extensiveness was probable. Yale quarry on the other hand offered the most out of all the options. First, Yale quarry was the nearest, being only half a mile south of the reservoir. The rocks were massive with cross-bedding tendency and there was evidence of thick bed first class rocks[9]. Throughout the explorations, Yale quarry kept showing promising results. The quarry offered a consistent deposit of bluestone with nearly horizontal strata of varying thickness separated by thin sheets of green shale. The bluestone varied in weight and density showed satisfactory soundness fit for working. The stratification of bluestone varies from 1 inch to 4 feet thick. The bluestone was found outcropping on the face of a bank for 2000 feet long, varying in height from 10 to 40 feet. The excavation at the Yale quarry proved to be successful and furnished all the material for the different classes of concrete and cyclopean masonry at the reservoir[10].

The acquisition of Yale quarry went through several appraisals, one in particular reached Supreme court level. In a publication titled Stone (vol.32) from 1911 highlights the appraisals for several quarries surrounding the reservoir[11]. Yale quarry or Yale farm originally belonged to Mr. and Mrs Yale who sold it to “the syndicate” Jerome H.Buck and James P. Mcgovern, New Yorkers, for a small price[12]. Buck acquired the property for speculative purposes. At the hearing with Commissioners of Appraisals, witnesses produced by the claimants testified that the value of the quarry is higher based on the fact that most of the stones used at the reservoir came from the Yale quarry. The city in advertising the contract for the reservoir gave the rights to the contractors to take the stone from the quarry instead of going to the open market. The city’s witness gave the quarry a value of $7000-$7100, stating that at the time the quarry was acquired there was no market value. The claimant on the other hand gave a value of $960,000 to $1,963,000. After a number of hearings, the settlement was awarded $27,500 which both sides rejected.

The labor intensive process of constructing the Ashokan reservoir required many workers. New immigrants coming from Italy, Ireland, Eastern European, and African-American from the South moved north to begin working at the reservoir. While there were not many records regarding the work at the Yale quarry, some figures showed the dangers and extensive labor needed to acquire the stones. The Engineering Record, Building Record, and Sanitary Engineer (1910) stated that the output of the quarry is limited to demand but can be increased as much as fifty percent if needed. A total of 240 men are employed on two 8 hour shifts. One of them started work at 6 a.m. and the second at 9 a.m.. The work at the quarry was under the guidance of superintendent E.W. Anderson[13]. The work at the quarry mainly consisted of acquiring the stone with the help of explosives and the hard labor of transporting it back to the reservoir site which sits about 2 miles north. For example, the transportation from the quarry requires three groups of twelve men and one foreman to load the skips with the help of the derricks[14]. Unfortunately, the dangerous work at the quarry also resulted in some deaths. A court appeal filed by MacArthur Bros. and Winston & Co. against New York City from 1918 revealed the death of a worker on site. In a settlement against Winston & Co., Germano P. Baccelli from the Italian consul represented Domenico Semproni, the deceased worker. At the time of his death, Semproni earned a weekly wage of $8.65. The settlement stated that Semproni acquired injuries while digging a bay of clay and gravel when a stone fell and hit him which caused a blow that resulted in death on February 27th 1915. The settlement began with $1000 cash. Later, the settlement also mentioned the widow and dependents of Semproni have been receiving cash awards throughout the settlement process. The award amounted to a total of $323.12; for 56 weeks from February 27th 1915 to March 25th 1916 every week the widow and dependents received $11.56. Ernesta Calamari, the widow aged 45, received 30% of the weekly payment ($2.60). The next in line was Semproni’s eldest daughter, Pasqua Semproni, aged 14 who received $0.635. The rest of Semproni’s dependents were Regina, Paolo, Maria, and Giuseppa (aged 12,10,5, and 3). The minor dependents respectively received compensation until the age of 18. At the time, the only living relative residing in the United States was Antonio, Semproni’s eldest son who was also employed by the company. Semproni’s body was shipped to Kingston on a railroad and was buried in a grave in St. Mary’s, Kingston cemetery. The company also paid for the cost of his burial which amounted to $90[15].

CURRENT STATE OF THE SITE: YALE QUARRY

Today, the Yale quarry area is known as the Ashokan quarry trail. The area maintains to be behind the original taking line and a protected area by NYC Department of Environmental Protection recently opened to the public. To access the trail, an entrance with parking is located on the north eastern tip of the site. The trail creates a two mile loop with several artifacts and access to the Ashokan high point. Around 0.3 miles after the entrance hikers encounter the first ruins which are located on a higher ground. The ruin used to house explosives for the quarry. Following a sharp left, comes the highest point of the quarry or the Ashokan high point. On the 0.6 the trail began its loop back on a descending path following the path of the old railroad tracks. The official trail does not include the loading area for the old railroad and remnants of the steel skips. To visit this area, hikers must go off trail towards the northern part of the quarry.

The current state of the quarry shows the extensive stone mining as the bottom of the quarry creates a large concave hole, which is frequently full of water. The trail is also hard to access especially for disabled hikers due to the lack of a clear path. Furthermore, the area seems visibly unkempt as there is a lot of household waste around the site.

CREATE

Last, the most important part of the construction of the reservoir is the creation. The birth of the reservoir is a story that involves massive extraction of resources with unpaid dues for the community and the creators–the thousands of workers of the reservoirs. The reservoir reveals our greed towards resources including the laborers that has brought us to the point of endangerment in the forms of environmental damage and social inequalities. The grim history of excavation and extraction of the reservoir should serve as a reminder of injustices during its creation, however the reservoir remains to be an extraordinary human creation. Since the full operation of the reservoir in 1915, the reservoir has provided millions of gallons of water to New York City. The creation of the reservoir serves as an inspiration for the reparations of the community surrounding the reservoir.

This project seeks to create an alternative architecture school network that integrates with the local community to rethink our relationship with resources through the act of making and waste management. Through the use of local resources and waste the school fortifies the economy of the community. The current state of the surrounding towns of the reservoir lacks access to resources for everyday needs. However, the town itself is rich in resources such as agricultural production. Furthermore, the waste produced adds to the list of resources instead of going to a recycling center outside of the community or a landfill. In this exercise, the community and students are asked to rethink their relationship with material resources. They are asked to rethink a materials life cycle starting from excavation, extraction, and the creation of the product. The language of excavation, extraction, and creation is also repeated throughout the architecture. The materials used for construction also retain accessibility as one of its key points. The toolkits developed include: bins spread throughout the area, storage units, an accessible pathway for the trail, rest points, makerspace compound, gathering area, and a housing compound.

[1] “Croton & Catskill/Delaware Watersheds,” Watershed Agricultural Council, February 7, 2023, https://www.nycwatershed.org/about-us/overview/croton-catskilldelaware-watersheds/.

[2]Stephen M. Silverman and Raphael D. Silver, The Catskills: Its History and How It Changed America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2015), 184.

[3] “Building the Ashokan Reservoir,” Public Water, http://public-water.com/story-of-nyc-water/ashokan-reservoir/.

[4] Silverman and Silver, 186.

[5] Silverman and Silver, 187.

[6] “Lowest Bid Loses Ashokan Contract,” The New York Times, August 27, 1907, pp. 1-14, 1.

[7] The Engineering Record, Building Record and Sanitary Engineer, vol. 61 (New York, NY: McGraw Publishing Co., 1910), 404-405.

[8] Lazarus White, The Catskill Water Supply of New York City ( John Wiley, 1913), 148 & 170.

[9] Charles P Berkey, “Quality of Bluestone Near the Ashokan Dam,” The School of Mines Quarterly, A Journal of Applied Science 29 (1908): pp. 149-158, 153.

[10] The Engineering Record, Building Record and Sanitary Engineer, vol. 6, 404-405.

[11] Stone (United States, Stone Magazine Review Publishing Company, 1911), 367.

[12] New York Supreme Court Appellate Division Third Department (1915).

[13] The Engineering Record, Building Record and Sanitary Engineer, vol. 6, 404-405.

[14] White, 148 & 170.

[15] Court of Appeals 1918 (1917), 941.