Constructing Palates, Constructing Spaces: Modernity through Food and Architecture in Late Colonial Dutch East Indies

Spring 24

Type: Academic research

Class: Feasting and Fasting (Ateya Khorakiwala)

Status: Done

Class: Feasting and Fasting (Ateya Khorakiwala)

Status: Done

The early twentieth century marked a significant turning point for the Dutch East Indies. Amidst the global wave of decolonization, an increasing questioning of national identity became central to both the colonizers and the colonized. Furthermore, the imperialist powers had extended colonization to modernization. [1] This progression was partly brought up because of the changing perception of colonization in the West, which demanded an ethical responsibility towards colonial subjects. The French termed it mission civilisatrice, the British ‘white man’s burden’ and the Dutch East Indies implemented Ethical Policy (1901). [2] The imperial powers saw that it was their responsibility to improve the welfare of their colonial subjects by uplifting the indigenous population and bringing them toward modernization. The progress towards modernizing the colony was not a linear process. From the colonizer’s end, there was an ethical dilemma between uplifting the colony and rising nationalism (‘Dutchness’ [3]) that required the colonizers to distance themselves from the colonized. The colonizer also imposed a spectrum of hybridization towards forming the colony’s identity. Hybridization was a tool to further the Dutch colonial government’s mission to modernize and unite the colony. The hybridization happened between varying spectrums of native, immigrant, and Western cultures. In particular, the mixing between Western-native cultures was seen as beneficial only to the colonized to uplift them from their primitive state, to assimilate, and eventually be absorbed into the colonizers' dominant identity.[4]

To bring the colonial government’s vision to life, food and architecture were important apparatuses in implementing modernity. The colonial construct believed food and architecture reveal a society’s state in evolution. While architecture explains the past and future of society, gastronomic habits distinguish physiological refinement, which establishes a vertical hierarchy amongst the colony.[5] Prior to rampant global imperialism, people of different class statuses in the same region were more likely to have similar eating habits. The availability of imported goods allowed colonizers to distinguish their eating habits and highlighted their ‘Europeanness’ or in this case ‘Dutchness’. Beyond imported edible commodities, modern architectural practices also became available to the colony following the same pattern of Westernization. The process of modernizing architecture in the Dutch East Indies reflected the intricacy of uplifting yet distancing from the colonial subjects. The colonial sentiment was apparent in the scope of private domestic spaces, segregated public spaces, and public spaces available to all in the colony. Thus, the late colonial period in the Dutch East Indies presented increasingly imported gastronomic habits and the development of modern architecture in a complex interplay of colonial identities that uplifted and distanced in the name of modernity.

From the 1900s to the 1930s, the Dutch East Indies experienced a notable surge in the European community. This growth was particularly pronounced among women, with the female population increasing from 600 per 1000 men in the 1900s to 900 per 1000 men by the 1930s. The influx of totok (Dutch-born) women from the Netherlands played a pivotal role in this rapid demographic shift. The European society was predominantly concentrated in Java, where 80% of the European population resided.[6] Moreover, the urban landscape of the Dutch East Indies was especially significant for women, more so than for men. This trend extended to Dutch-born women, who primarily inhabited the six major cities of Java: Batavia, Bandung, Semarang, Yogyakarta, Surakarta, and Surabaya.[7] These cities served as focal points for the European population and hubs where Western influences emanated throughout the colony.

It was uncommon for European women to be professionally employed.[8] Typically, they arrived in the colony in search of marriage, which led to their role as housewives. The increase in the Dutch female population meant a pivotal change in the domestic realm. Before arriving in the colony, Dutch women received education from institutions and manuals that insinuated their duty there. Colonial School for Girls and Women (Koloniale School voor Meisjes en Vrouwen) was founded in 1920 to prepare women coming to the colony. The school was founded based on the concern that women lack preparation for coming to a faraway land with different climates and living configurations. The school mainly targeted housewives and future housewives, preparing them about hygiene in the tropics, home nursing and first aid, cooking and managing household chores, interacting with native populations and servants, and learning the Malay culture.[9] The manuals written by Indo-European women and later totok[10] women described similar subjects such as etiquettes for interacting with native servants and described housewives' tasks beyond manual labor.[11] After all, as Bauduin described in Het Indische Leven (Indies Life, 1927), “a decent European in the Indies does not do manual labor or homework because of his prestige, and secondly, it is much too hot for that.”[12] Above manual labor and in line with the ‘ethical’ colonial agenda, Dutch women's responsibilities in the colony were to civilize the colony and bring them towards modernity. As Locher-Scholten puts it, “Women were responsible for civilizing the untamed colonial community, as part of what was considered to be a ‘civilizing mission’, they were instructed to uphold the values of white morality and prestige and to prevent the loosening of their husbands’ sexual standards. They had an obligation at home to educate not only their children, but their servants as well, and they had an important role in the development or the uplifting of the indigenous population in their surroundings.”[13] The role of Dutch women was to become the mother of the colony.

One of the most important pillars of modernity at the time was hygiene including health literacy and nutrition which put Dutch women at the forefront of the colonial mission. As the ‘mother’ of the colony, the role of Dutch women was not only to educate but also to govern the bodily functions and habits of their children. Hygiene, health, and nutrition were inherently tied to eating habits and practices. Moreover, the culinary culture in the colony revealed that hygiene practices were highly racialized. The implementation of modern hygiene and nutrition practices began in infancy. In the Netherlands, middle-class women hired wet nurses to satisfy the preferred nutritional values that breastfeeding provides; however, in the colony, this was not an option due to racial considerations. The European community feared native servants could contaminate their children with their harmful moral characteristics. Thus, the market for milk substitutes such as powdered milk and condensed milk grew in the Dutch East Indies. Foreign milk companies such as Omnia (Netherlands), Glaxo (New Zealand), and Nestle’s Lactogen and Milk Maid (Switzerland) were commonly available and advertised.[14] Furthermore, manuals for totok women also pointed out that children should not eat food from native servants.[15] The practice of keeping a distance from indigenous servants stemmed not only from concerns about the risk of physical contagion and disease transmission but also from apprehensions regarding moral influence.

Conversely, Western commodities such as milk served to elevate the colony. The small urban middle-upper class native women populations saw European motherhood practices as an emblem of modernity. In 1939 a publication for native women, Keoetamaan Istri (Wife’s priority), remarked on the accounts of a native middle-class mistress and her native servant regarding milk. The mistress delivered a lecture to the servant, emphasizing the significance of milk, when the servant expressed concern that milk makes the lower-class stomach sick. The inclusion of Western culinary items like milk in publications aimed at natives, such as Keoetamaan Istri, mirrored the trend seen in periodicals for Dutch women such as De Huisvrouw in Indie (Figure 1). Both publications listed local dairies, quality, and cost of milk. Milk posed as both a costly item and an acquired palate for natives. [16] Nonetheless, it served as a significant symbol of Western attributes and thus, modernity. In addition, the participation of native women in the consumption of Western goods signaled the emergence of a native middle-class demographic.

![]() (Figure 1) Advertisement for Nutricia milk. Source: Huisvrouw in Indië, no. 10, October 1932.

(Figure 1) Advertisement for Nutricia milk. Source: Huisvrouw in Indië, no. 10, October 1932.

Another instance of shifting culinary preferences within the Dutch East Indies European community linked the colony's private and public spheres. Prior to the influx of the European community, Rijsttafel (rice table) was commonly served in the European household. The availability of imported goods and an attempt to distinguish ‘Dutchness’ made canned food popular by the 1920s-1930s.[17] Rijsttafel emerged as a fusion of Dutch, indigenous, and pre-existing cultural influences in the colony, including Chinese, South Asian, and Arab elements. Rijsttafel involved a unique presentation of rice accompanied by an array of dishes spanning from vegetables to meat (Figure 2). Published in 1902, Nieuw volledig Oost-Indisch kookboek (New complete East Indies cookbook), covers the complex nature of Rijsttafel menu. The subtitle “Recepten voor de volledige Indische Rijsttafel, zuren, gebakken, vla's, confituren, ijssoorten, met een kort aanhangsel voor Holland” suggests the variety of possible dishes to accompany rice such as pickles, fried, custards, jams ,and ice cream. Prominent recipes from the cookbook that exemplify the blend of cultures were various types of kerrie and atchar (curry and pickle, South-Asian), frikadel djagong (deep fried corn, Dutch), bah mi (noodle dish, Chinese), and many more. While the dishes in the cookbook may have originated from outside the colony, they have since transformed into distinctly Dutch East Indies creations, contributing to the intricacy of Rijsttafel. The publication Het Indische Leven describes the relevance of a housewife serving Rijsttafel to her husband and guests which would reward her with numerous compliments.[18]

![]() (Figure 2) European family enjoying Rijsttafel, Bandung, 1936.

(Figure 2) European family enjoying Rijsttafel, Bandung, 1936.

Nevertheless, by the 1920s-1930s, Rijsttafel was reserved for the weekends notably because of its overwhelming excessiveness in taste[19] and more importantly, shift towards a more European diet. The availability of food preservation such as canned goods and refrigeration and increased imports allowed a European diet in the Indies. During the weekdays, Dutch households served European dishes such as chicken and apple sauce, red cabbage, and sauerkraut.[20] A trade report from the years 1924-1929 (Figure 3) documented the canned goods exported by the United States as follows: meat products, milk (condensed and evaporated), fish (salmon, sardines, shellfish), vegetables (asparagus, beans, corn, peas, soups, tomatoes), and fruits (berries, apple and apple sauce, apricots, cherries, prunes, plums, peaches, pears, pineapples, fruits for salads, and preserves).[21] While the demand varied from year to year, overall, by 1929, the demand for most items increased.

![]() (Figure 3) Trade report of Dutch East Indies canned food import 1924-1929.

(Figure 3) Trade report of Dutch East Indies canned food import 1924-1929.

Race, class, and geography limited the consumption of imported goods. A commerce report, released by the United States Department of Commerce in 1930, examined the scale of canned goods consumption.[22] The report observed that natives faced limited access to canned goods due to their high cost and unfamiliar taste preferences. Imported goods were predominantly absent from native markets, with only inexpensive options like sardines accessible to native populations, primarily at Chinese shops. The consumption of luxury items such as meat was limited to the Chinese and European populations. Although slaughterhouses were present in urban areas, frozen meat imports were sourced from Australia and New Zealand, canned corned beef from South America, and sausages, ham, and bacon from Europe. Likewise, locally grown vegetables were available, however, Europeans insisted on canned vegetables from Dutch brands selling cauliflower, peas, and beans. While American canned vegetable brands were accessible, Dutch brands were generally more prevalent in quantity. Annually, the Dutch East Indies purchased a total of 120,000 cases of canned fruits, primarily supplied by California. Another sought-after import was dairy products, with canned milk like sweetened condensed milk in high demand in native and Chinese markets, while evaporated and unsweetened condensed milk catered to European preferences. Butter imports mainly originated from Australia, although some butter and cheese came from the Netherlands. Additionally, products like biscuits and confectionery were sourced from Great Britain and the Netherlands mainly for the Chinese and European markets. Moreover, imported goods for European consumption were concentrated in urban areas and retailed in Chinese "toko" or shops. Establishments catering to the European market are typically well-appointed shops, offering a wide selection of canned or preserved foods, wines, liquors, and cigarettes. Occasionally, they also stock fresh fruits and may even feature an electric refrigerator to store butter, cheese, fruit, and ice cream.

On the other hand, Rijsttafel continued to thrive in the public sphere due to the growing interest in tourism. During the initial decades of the 20th century, coinciding with the implementation of the Ethical Policy, the Dutch colonial administration decided to open the colony to a larger market, resulting in a surge in the European population. This population growth was attributed to both long and short-term migration to the Dutch East Indies. The abolition of the trade monopoly enabled private entrepreneurs to prolong their stays in the colony.[23] Furthermore, the relaxation of travel restrictions [24], coupled with the increasing recognition of the Dutch East Indies in Western popular media, prompted the colonial government to recognize the growing potential of tourism. The Dutch colonial administration viewed tourism as a key component of the ongoing implementation of the Ethical Policy, aiming not only to reap economic benefits but also to improve the welfare of colonial subjects by exposing the colony to European modernities. Tourism also played a significant role in the broader global endeavor of civilizing the colonies, allowing the Dutch colonial state to showcase the grandeur of their colony to Europeans. Tourism allowed the colonial state to highlight infrastructural development and its role as a benevolent ruler.

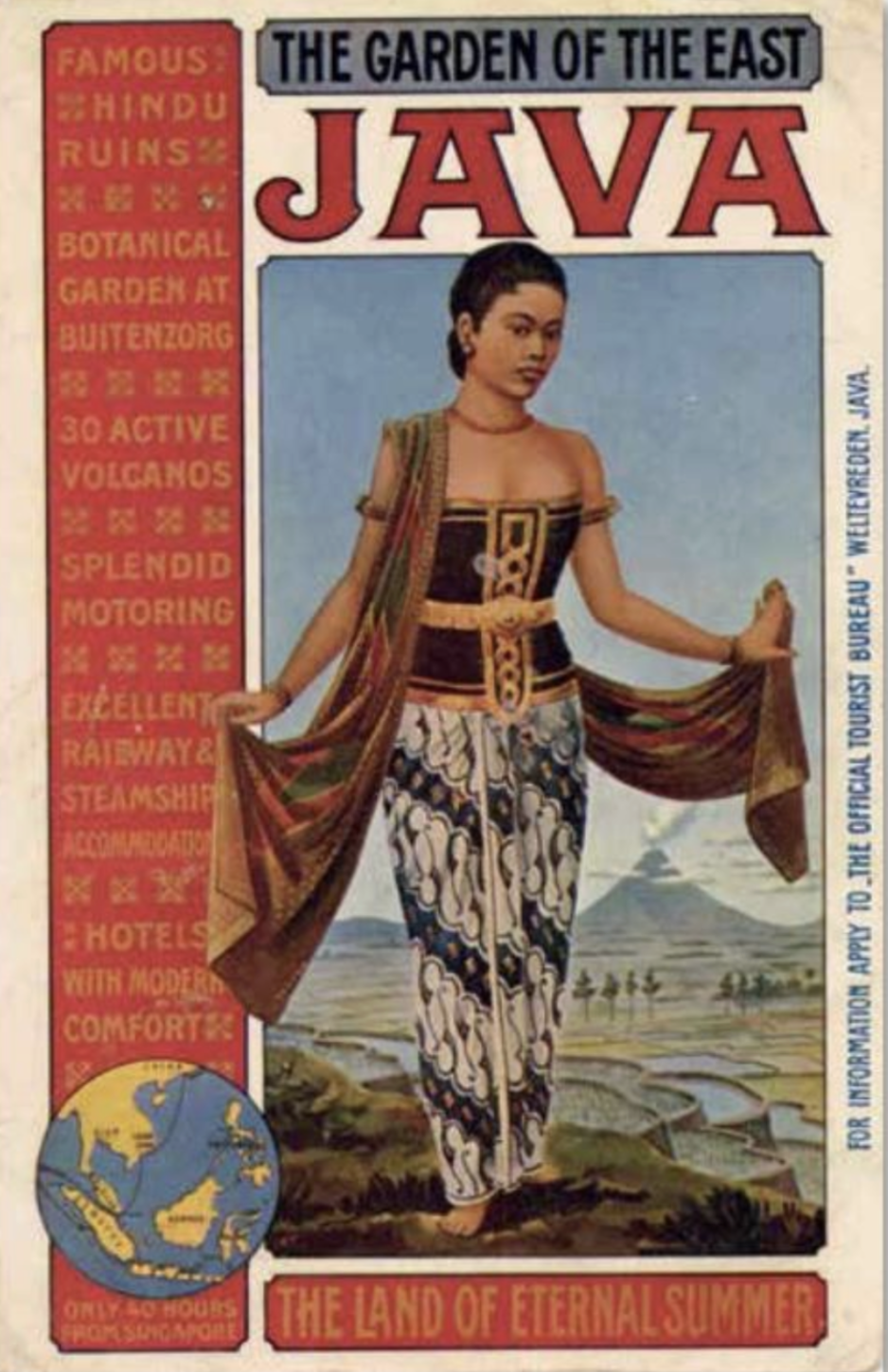

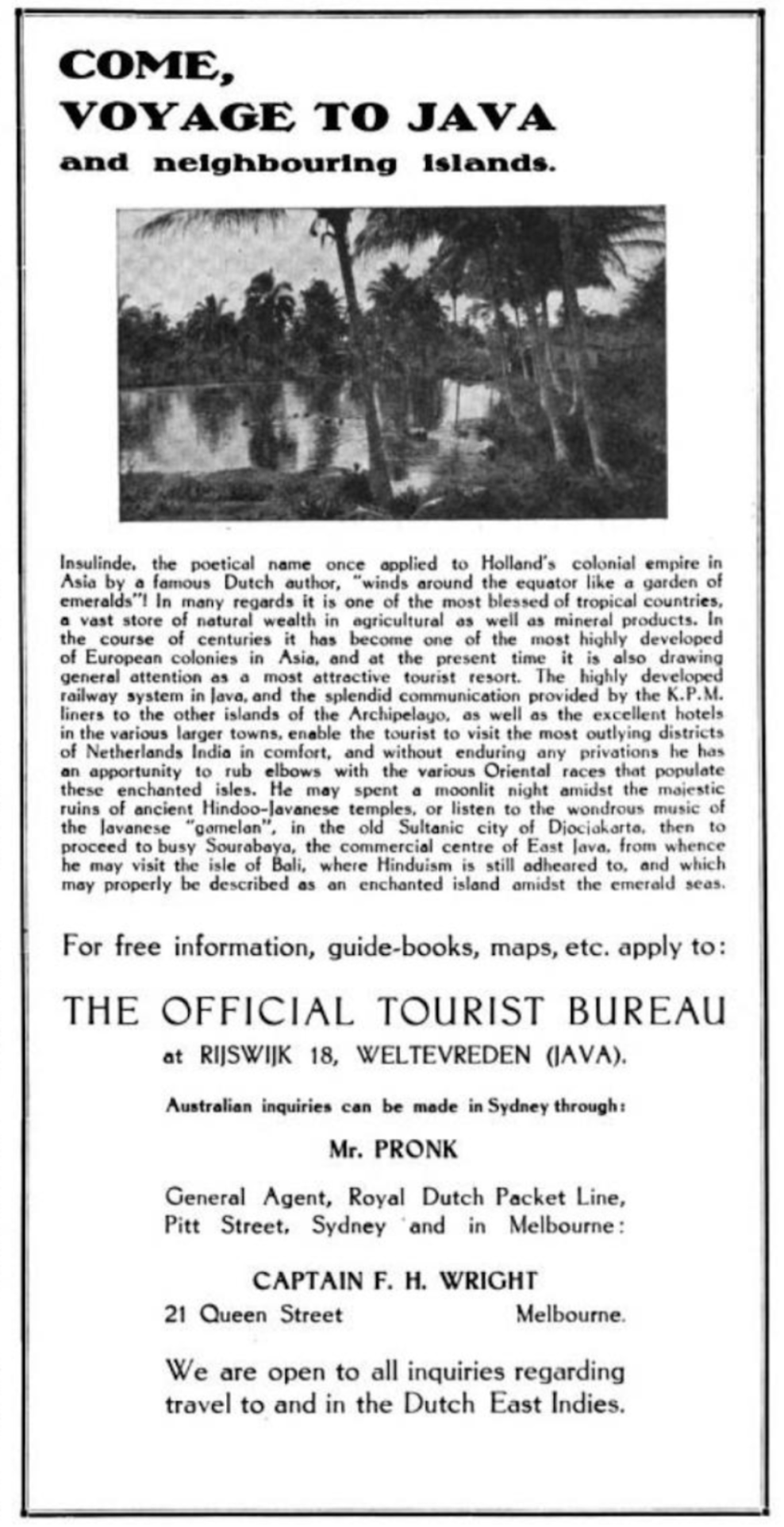

Rijsttafel was an important apparatus for the colonial touristic venture. The interest in tourism led to the creation of the Official Tourists Bureau in 1908[25] initially based at the infamous Hotel des Indes[26], a non-profit institution subsidized by the colonial government.[27] A postcard from 1910 (Figure 4) depicts the Official Tourists Bureau promoting Java's historical and ecological features, such as "Famous Hindu ruins" and "30 active volcanoes," alongside technological advancements like "excellent railway and steamship" facilities, and notably, Western-standard accommodations, such as "Hotels with modern comfort." Another advertisement from the 1920s (Figure 5) describes a similar attitude toward tourism in the colony “In the course of centuries it has become one of the most highly developed of European colonies in Asia, and at the present time it is also drawing general attention as a most attractive tourist resort. The highly developed railway system in Java, and the splendid communication provided by the K.P.M. liners to the other islands of the Archipelago, as well as the excellent hotels in the various larger towns, enable the tourist to visit the most outlying districts of Netherlands India in comfort, and without any privation he has an opportunity to rub elbows with the various Oriental races that populate these enchanted isles.” The contrast between the colony's exotic allure and the availability of Western-standard accommodations shaped tourists' expectations in the Dutch East Indies. Similarly, the acceptance of Rijsttafel as a component of the colony's identity added to the exotic appeal for European tourists which was often served in modern establishments. Despite Rijsttafel being a highly anticipated component of the culinary adventure in the Dutch East Indies, efforts to restrict the consumption of colonial identities persist. The publication Het Indische Leven noted the strangeness of eating over-stimulating spice in the tropics served with ice-cold beer which would cause indigestion. Thus, the consumption of Rijsttafel should be limited to weekends only. Moreover, the publication suggests the importance of proper cuisine to make up for the lack of other pleasures in the colony.[28]

![]() (Figure 4) Advertisement for tourism to Java from 1910s.

(Figure 4) Advertisement for tourism to Java from 1910s.

![]() (Figure 5) Advertisement by the Official Tourist Bureau from the 1920s.

(Figure 5) Advertisement by the Official Tourist Bureau from the 1920s.

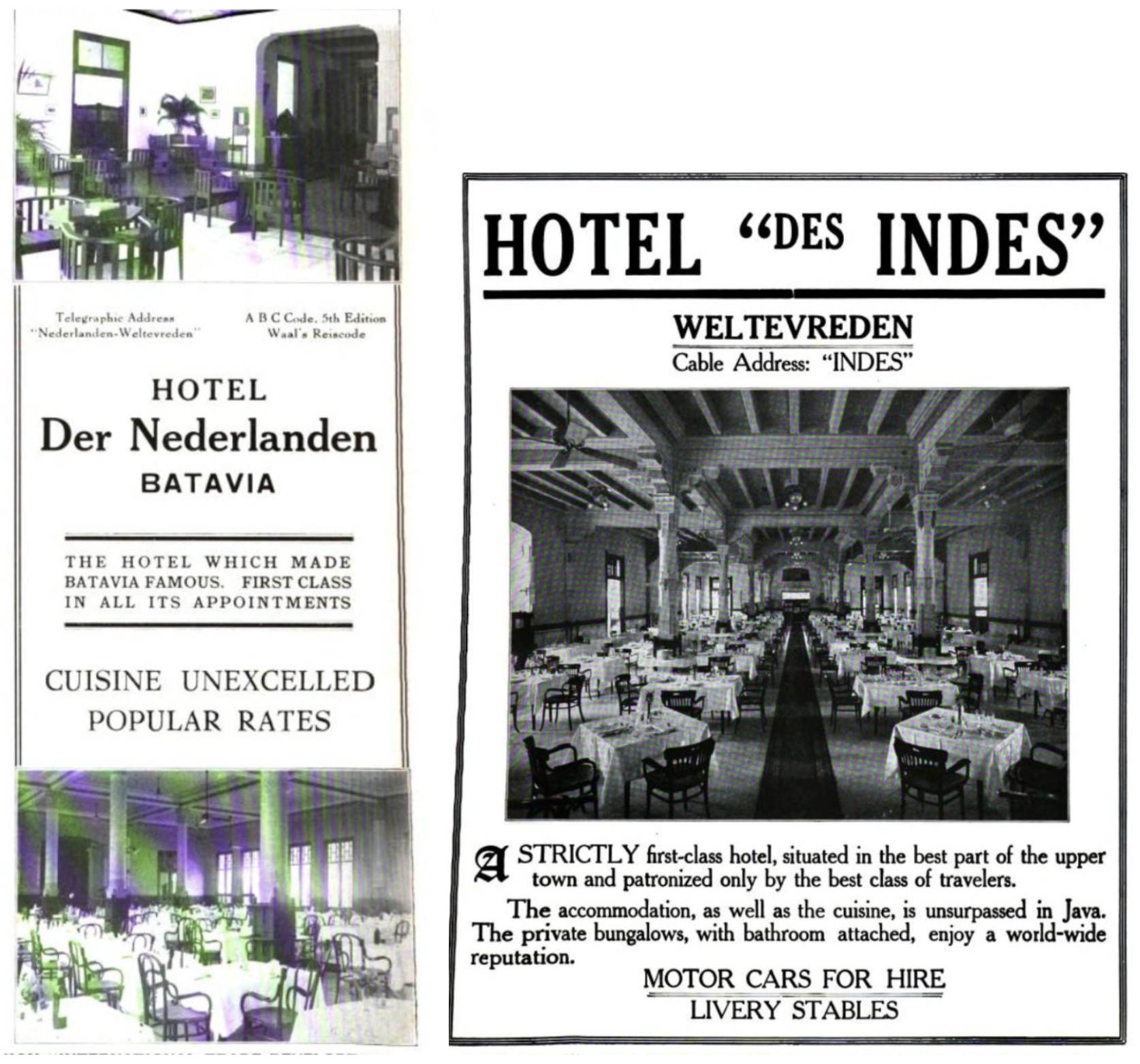

The popularity of Rijsttafel grew alongside the development of modern architecture in the Dutch East Indies. Rijsttafel served as a significant draw for numerous Western hotels as part of culinary tourism.[29] Unlike its portrayal in domestic settings, Rijsttafel represented abundance and luxury in the public sphere of the colony. Moreover, the abundance that Rijsttafel represented in the public realm also came with the array of native servants for each dish served (Figure 6). Well-known hotels throughout Java such as Hotel der Nederlanden and Hotel des Indes, advertised their cuisine as one of their selling points (Figure 7). While both hotels advertised their excellent cuisine, the imagery featured in the advertisements focused on the dining hall. The significance of the culinary experience extended beyond just the food to include the surrounding environment. The dining hall served as a crucial architectural element enhancing the experience for Western tourists. The familiarity of modern comfort and hygiene subdued colonial anxieties allowing European tourists to be Western in the colony. Thus, the demand for modern architecture increased as a result of tourism.

![]() (Figure 6) Rijsttafel at Hotel der Nederlanden.

(Figure 6) Rijsttafel at Hotel der Nederlanden.

![]() (Figure 7) Advertisements of Hotel des Indes and Hotel der Nederlanden.

(Figure 7) Advertisements of Hotel des Indes and Hotel der Nederlanden.

Simultaneously, a burgeoning architectural movement throughout 1907-1917 in the Netherlands spurred Dutch architects to explore opportunities in the Dutch East Indies. The Amsterdam School pursued a more artistically expressive architecture, while the more prevalent De Stijl movement favored rational and abstract design principles.[30] Despite lacking a firm theoretical or social foundation, the Amsterdam School prioritized the individual designer and unrestrained creative expression in its designs.[31] The appeal of unlimited space and freedom of expression attracted numerous Amsterdam School architects to the Dutch East Indies. However, the architectural style brought by the Amsterdam School to the Dutch East Indies often reflected cultural imperialism. Although not fully realized, the influence of the Amsterdam School was significant in shaping the development of the New Indies Style.[32]

The dining hall at Hotel Des Indes was one of the many examples of the development of the New Indies Style. Prominent architects from the New Indies movement worked on Hotel des Indes. One notable figure was P.A.J. Moojen. Moojen was the first independent architect who worked in a modern architecture style in the Dutch East Indies and many of his contemporaries considered him the first modern ‘Indische’ architect.[33] Prior to Moojen, architects practicing in the colony often imported European architecture while ignoring local cultures and climatic conditions. Moojen propelled the movement by maintaining the building methods of the Dutch East Indies while improving their architecture with Western influences. New Indies Style architecture can be characterized by the tropical climate adaptation of architectural movements seen in Europe at the time. Elements popular in the Art Deco movement such as white facades and horizontal articulation were commonly seen in New Indies Style. However, European elements such as flat roofs and tall buildings were uncommon due to climatic reasons and land availability.[34] Before the renovation, Hotel Des Indes embraced the colonial style with classical columns and arches. In 1906, P.A.J. Moojen assisted by S. Snuyf, renovated and brought modern influence such as the geometric decoration in the dining room.[35] The dining room at Hotel des Indes accommodated nearly 400 persons, connected to an extensive lounge.[36]

Part of the introduction of the modern architecture movement was the incorporation of modern technology. By 1913, the dining hall at Hotel des Indes had been equipped with electric fans and lamps. On the opposite side of the dining hall, the kitchen was furnished with large refrigerators, Western-style stoves, and baking apparatuses to prepare a variety of European dishes. Additionally, European machinery for kneading, washing, and polishing was also available. Hotel des Indes featured separate departments for pastry, bread baking, chicken and fish preparation, potatoes and vegetables, and Rijsttafel preparation (Figure 8).[37] Similarly, at Hotel der Nederlanden, the kitchen garnered praise for its extensive refrigeration rooms and European head chefs (Figure 9).[38] However, the native workers who prepared and served the dishes were often overlooked. Their roles were mainly in the background: in the kitchen, they functioned as another set of food preparation apparatus, while in the dining hall, they served as another fixture to complete the dining experience. The preparation, serving, and consumption of Rijsttafel juxtaposed European patrons with natives. Western architecture and technologies further accentuated the dichotomy between the served and the servants.

![]()

(Figure 8) Hotel des Indes kitchen showcasing European cooking equipments.

![]() (Figure 9) Hotel der Nederlanden kitchen with European chef 1930.

(Figure 9) Hotel der Nederlanden kitchen with European chef 1930.

The introduction of imported European commodities such as architecture and food extended to the native population as part of the Dutch colonial mission to uplift and assimilate the colony. These imported European goods, seen as emblems of modernity, continued to gain popularity beyond domestic and touristic spaces. Recognizing the emergence of a native middle class as an opportunity, the Dutch colonial government sought to create a new market within the colony. Among numerous strategies, the establishment of fairs was one of the most significant tactics for introducing modernity. Unlike colonial fairs in the West, those in the colony served a distinct purpose. They aimed to promote the introduction of modernity and foster a vision of a united Dutch East Indies. The Gambir Fair in particular played a pivotal role in colonial propaganda. Before the Gambir Fair, other fairs in the colony already existed for industrial purposes. However, in the 1920s, Gambir Fair was reintroduced as a plan to integrate modern economic development.[39] Furthermore, the fair introduced modern culture such as leisure and entertainment through the consumption of modern products.[40] The Gambir Fair was unlike any other occasion in the colony before. Located at the heart of the urban fabric in Koningsplein (King’s Square), Batavia, the fair was open to everyone. It was monumental because it was a public space for every race supported by the Dutch government. For the first time, natives, Europeans, and other foreigners (Chinese and Arabs) celebrated the diversity of the colony. The objective of annual fairs such as the Gambir Fair was to civilize native populations through the consumption of Western culture[41], fostering a unified vision of the colony through modernity[42], and preparing them to be absorbed into the colonial empire.[43]

Modern architecture played a crucial role in realizing the Dutch colonial visions. Unlike the modern architecture at European standard hotels which was an adaptation of European architecture in the tropics, the architecture at Gambir Fair presented a novel blend of imported and local architecture. Elements of European architecture combined with native architecture including architecture from foreign Eastern cultures such as Chinese and Arab created a novel hybrid architecture (Figure 10). The architect of Hotel des Indes’s dining hall wrote in a Dutch newspaper for Batavia, D’Orient, regarding his astonishment at the architecture at Gambir Fair. Moojen wrote on the materiality and form of the pavilions at the fair. The structure of the fair combined silhouettes of traditional Indonesian architecture in a whimsical manner.[44] Moojen referred to the blend of architecture as Indonesian architecture instead of Dutch East Indies which signified a recognition of an identity separate from the Dutch empire and a unified vision of the colony. Later Moojen designed the Dutch East Indies pavilion at the Paris Colonial Exposition in 1931 inspired by the architecture of Gambir Fair (Figure 11). In addition, Gambir Fair celebrated modernity through modern technology such as electric lights (Figure 12).

![]() (Figure 10) Gambir Fair 1925.

(Figure 10) Gambir Fair 1925.

![]() (Figure 11) The Dutch Pavilion at Paris Colonial Exposition (1931).

(Figure 11) The Dutch Pavilion at Paris Colonial Exposition (1931).

The dichotomy between Dutch and native cultures was also evident through the juxtaposition of Dutch and native gastronomic culture. The practice of contrasting Dutch and native cultures proved to visualize not only a class and racial hierarchy but also what natives should desire. Native cuisine such as nasi goreng[45] existed alongside imported food brands such as Blue Band, Sun-Maid raisins, Coca-Cola, Victoria Biscuits and Heineken Beer.[46] Moreover, for an extra fare, rare Dutch cuisines such as pickled herring, rolmops, spekbokking, mackerel, mussels, Russian salad, Dutch cold cuts, kroket, and sausage rolls were available at exclusive restaurants.[47] The availability of imported goods did not mean they were within the financial and racial means of the native population. Additional fees and segregation were standard practices at the fair. Another aspect of food practices, hygiene, was also emphasized at the fair. Similar to hygiene propaganda for mothers in the domestic realm, the Dutch colonial government exhibited modern hygiene and sanitation practices that dealt with food preparation and other common diseases. For instance, at the Gambir Fair in 1930, a diorama illustrating the risks posed by flies around uncovered food at a warung[48] showcased typical unhygienic practices among natives (Figure 13).[49] Exposing and contrasting native and European cultures implied the primitiveness of the native population. Nonetheless, projecting modernity on the native population was important to the colonial mission of uplifting.

![]() (Figure 12) Gambir Fair entrance showcases the use of modern technology, such as light.

(Figure 12) Gambir Fair entrance showcases the use of modern technology, such as light.

![]() (Figure 13) Exhibition of hygiene at Gambir Fair, depicting a scene at a warung.

(Figure 13) Exhibition of hygiene at Gambir Fair, depicting a scene at a warung.

In the late colonial period of the Dutch East Indies, the intricate relationship between architecture and gastronomic culture serves as a lens through which we can understand the complexities of colonial power dynamics, identity formation, and the pursuit of modernity. Imported commodities, in the form of both architectural designs and culinary practices, were tangible expressions of the power dynamics at play within the colony, symbolizing the colonizers' assertion of modernity and superiority. At the domestic level, Dutch women were tasked with the responsibility of civilizing the colony by instilling European values and habits, including culinary preferences that mirrored those of the colonizers. The domestic sphere reflected the gendered dynamics of colonial power, as Dutch women navigated between their roles as housewives and agents of colonial assimilation. In touristic venues, such as hotels and restaurants, the juxtaposition of native cuisines like Rijsttafel with modern architectural designs showcased the dichotomy of native and European existence. Here, architecture and gastronomy converged to create an exotic allure for European tourists while reinforcing colonial hierarchies and cultural dominance. Furthermore, events like the Gambir Fair exemplified the colonial government's efforts to uplift the native population through the introduction of European culture and commodities. The complexities of power in the Dutch East Indies were manifested through the interplay of architecture and gastronomic culture, touching upon gender, race, and class dynamics within the colony. These imported commodities served as enduring reminders of the persistence of colonialism within the veneer of modernity.

*references availble upon request

To bring the colonial government’s vision to life, food and architecture were important apparatuses in implementing modernity. The colonial construct believed food and architecture reveal a society’s state in evolution. While architecture explains the past and future of society, gastronomic habits distinguish physiological refinement, which establishes a vertical hierarchy amongst the colony.[5] Prior to rampant global imperialism, people of different class statuses in the same region were more likely to have similar eating habits. The availability of imported goods allowed colonizers to distinguish their eating habits and highlighted their ‘Europeanness’ or in this case ‘Dutchness’. Beyond imported edible commodities, modern architectural practices also became available to the colony following the same pattern of Westernization. The process of modernizing architecture in the Dutch East Indies reflected the intricacy of uplifting yet distancing from the colonial subjects. The colonial sentiment was apparent in the scope of private domestic spaces, segregated public spaces, and public spaces available to all in the colony. Thus, the late colonial period in the Dutch East Indies presented increasingly imported gastronomic habits and the development of modern architecture in a complex interplay of colonial identities that uplifted and distanced in the name of modernity.

From the 1900s to the 1930s, the Dutch East Indies experienced a notable surge in the European community. This growth was particularly pronounced among women, with the female population increasing from 600 per 1000 men in the 1900s to 900 per 1000 men by the 1930s. The influx of totok (Dutch-born) women from the Netherlands played a pivotal role in this rapid demographic shift. The European society was predominantly concentrated in Java, where 80% of the European population resided.[6] Moreover, the urban landscape of the Dutch East Indies was especially significant for women, more so than for men. This trend extended to Dutch-born women, who primarily inhabited the six major cities of Java: Batavia, Bandung, Semarang, Yogyakarta, Surakarta, and Surabaya.[7] These cities served as focal points for the European population and hubs where Western influences emanated throughout the colony.

It was uncommon for European women to be professionally employed.[8] Typically, they arrived in the colony in search of marriage, which led to their role as housewives. The increase in the Dutch female population meant a pivotal change in the domestic realm. Before arriving in the colony, Dutch women received education from institutions and manuals that insinuated their duty there. Colonial School for Girls and Women (Koloniale School voor Meisjes en Vrouwen) was founded in 1920 to prepare women coming to the colony. The school was founded based on the concern that women lack preparation for coming to a faraway land with different climates and living configurations. The school mainly targeted housewives and future housewives, preparing them about hygiene in the tropics, home nursing and first aid, cooking and managing household chores, interacting with native populations and servants, and learning the Malay culture.[9] The manuals written by Indo-European women and later totok[10] women described similar subjects such as etiquettes for interacting with native servants and described housewives' tasks beyond manual labor.[11] After all, as Bauduin described in Het Indische Leven (Indies Life, 1927), “a decent European in the Indies does not do manual labor or homework because of his prestige, and secondly, it is much too hot for that.”[12] Above manual labor and in line with the ‘ethical’ colonial agenda, Dutch women's responsibilities in the colony were to civilize the colony and bring them towards modernity. As Locher-Scholten puts it, “Women were responsible for civilizing the untamed colonial community, as part of what was considered to be a ‘civilizing mission’, they were instructed to uphold the values of white morality and prestige and to prevent the loosening of their husbands’ sexual standards. They had an obligation at home to educate not only their children, but their servants as well, and they had an important role in the development or the uplifting of the indigenous population in their surroundings.”[13] The role of Dutch women was to become the mother of the colony.

One of the most important pillars of modernity at the time was hygiene including health literacy and nutrition which put Dutch women at the forefront of the colonial mission. As the ‘mother’ of the colony, the role of Dutch women was not only to educate but also to govern the bodily functions and habits of their children. Hygiene, health, and nutrition were inherently tied to eating habits and practices. Moreover, the culinary culture in the colony revealed that hygiene practices were highly racialized. The implementation of modern hygiene and nutrition practices began in infancy. In the Netherlands, middle-class women hired wet nurses to satisfy the preferred nutritional values that breastfeeding provides; however, in the colony, this was not an option due to racial considerations. The European community feared native servants could contaminate their children with their harmful moral characteristics. Thus, the market for milk substitutes such as powdered milk and condensed milk grew in the Dutch East Indies. Foreign milk companies such as Omnia (Netherlands), Glaxo (New Zealand), and Nestle’s Lactogen and Milk Maid (Switzerland) were commonly available and advertised.[14] Furthermore, manuals for totok women also pointed out that children should not eat food from native servants.[15] The practice of keeping a distance from indigenous servants stemmed not only from concerns about the risk of physical contagion and disease transmission but also from apprehensions regarding moral influence.

Conversely, Western commodities such as milk served to elevate the colony. The small urban middle-upper class native women populations saw European motherhood practices as an emblem of modernity. In 1939 a publication for native women, Keoetamaan Istri (Wife’s priority), remarked on the accounts of a native middle-class mistress and her native servant regarding milk. The mistress delivered a lecture to the servant, emphasizing the significance of milk, when the servant expressed concern that milk makes the lower-class stomach sick. The inclusion of Western culinary items like milk in publications aimed at natives, such as Keoetamaan Istri, mirrored the trend seen in periodicals for Dutch women such as De Huisvrouw in Indie (Figure 1). Both publications listed local dairies, quality, and cost of milk. Milk posed as both a costly item and an acquired palate for natives. [16] Nonetheless, it served as a significant symbol of Western attributes and thus, modernity. In addition, the participation of native women in the consumption of Western goods signaled the emergence of a native middle-class demographic.

Another instance of shifting culinary preferences within the Dutch East Indies European community linked the colony's private and public spheres. Prior to the influx of the European community, Rijsttafel (rice table) was commonly served in the European household. The availability of imported goods and an attempt to distinguish ‘Dutchness’ made canned food popular by the 1920s-1930s.[17] Rijsttafel emerged as a fusion of Dutch, indigenous, and pre-existing cultural influences in the colony, including Chinese, South Asian, and Arab elements. Rijsttafel involved a unique presentation of rice accompanied by an array of dishes spanning from vegetables to meat (Figure 2). Published in 1902, Nieuw volledig Oost-Indisch kookboek (New complete East Indies cookbook), covers the complex nature of Rijsttafel menu. The subtitle “Recepten voor de volledige Indische Rijsttafel, zuren, gebakken, vla's, confituren, ijssoorten, met een kort aanhangsel voor Holland” suggests the variety of possible dishes to accompany rice such as pickles, fried, custards, jams ,and ice cream. Prominent recipes from the cookbook that exemplify the blend of cultures were various types of kerrie and atchar (curry and pickle, South-Asian), frikadel djagong (deep fried corn, Dutch), bah mi (noodle dish, Chinese), and many more. While the dishes in the cookbook may have originated from outside the colony, they have since transformed into distinctly Dutch East Indies creations, contributing to the intricacy of Rijsttafel. The publication Het Indische Leven describes the relevance of a housewife serving Rijsttafel to her husband and guests which would reward her with numerous compliments.[18]

Nevertheless, by the 1920s-1930s, Rijsttafel was reserved for the weekends notably because of its overwhelming excessiveness in taste[19] and more importantly, shift towards a more European diet. The availability of food preservation such as canned goods and refrigeration and increased imports allowed a European diet in the Indies. During the weekdays, Dutch households served European dishes such as chicken and apple sauce, red cabbage, and sauerkraut.[20] A trade report from the years 1924-1929 (Figure 3) documented the canned goods exported by the United States as follows: meat products, milk (condensed and evaporated), fish (salmon, sardines, shellfish), vegetables (asparagus, beans, corn, peas, soups, tomatoes), and fruits (berries, apple and apple sauce, apricots, cherries, prunes, plums, peaches, pears, pineapples, fruits for salads, and preserves).[21] While the demand varied from year to year, overall, by 1929, the demand for most items increased.

Race, class, and geography limited the consumption of imported goods. A commerce report, released by the United States Department of Commerce in 1930, examined the scale of canned goods consumption.[22] The report observed that natives faced limited access to canned goods due to their high cost and unfamiliar taste preferences. Imported goods were predominantly absent from native markets, with only inexpensive options like sardines accessible to native populations, primarily at Chinese shops. The consumption of luxury items such as meat was limited to the Chinese and European populations. Although slaughterhouses were present in urban areas, frozen meat imports were sourced from Australia and New Zealand, canned corned beef from South America, and sausages, ham, and bacon from Europe. Likewise, locally grown vegetables were available, however, Europeans insisted on canned vegetables from Dutch brands selling cauliflower, peas, and beans. While American canned vegetable brands were accessible, Dutch brands were generally more prevalent in quantity. Annually, the Dutch East Indies purchased a total of 120,000 cases of canned fruits, primarily supplied by California. Another sought-after import was dairy products, with canned milk like sweetened condensed milk in high demand in native and Chinese markets, while evaporated and unsweetened condensed milk catered to European preferences. Butter imports mainly originated from Australia, although some butter and cheese came from the Netherlands. Additionally, products like biscuits and confectionery were sourced from Great Britain and the Netherlands mainly for the Chinese and European markets. Moreover, imported goods for European consumption were concentrated in urban areas and retailed in Chinese "toko" or shops. Establishments catering to the European market are typically well-appointed shops, offering a wide selection of canned or preserved foods, wines, liquors, and cigarettes. Occasionally, they also stock fresh fruits and may even feature an electric refrigerator to store butter, cheese, fruit, and ice cream.

On the other hand, Rijsttafel continued to thrive in the public sphere due to the growing interest in tourism. During the initial decades of the 20th century, coinciding with the implementation of the Ethical Policy, the Dutch colonial administration decided to open the colony to a larger market, resulting in a surge in the European population. This population growth was attributed to both long and short-term migration to the Dutch East Indies. The abolition of the trade monopoly enabled private entrepreneurs to prolong their stays in the colony.[23] Furthermore, the relaxation of travel restrictions [24], coupled with the increasing recognition of the Dutch East Indies in Western popular media, prompted the colonial government to recognize the growing potential of tourism. The Dutch colonial administration viewed tourism as a key component of the ongoing implementation of the Ethical Policy, aiming not only to reap economic benefits but also to improve the welfare of colonial subjects by exposing the colony to European modernities. Tourism also played a significant role in the broader global endeavor of civilizing the colonies, allowing the Dutch colonial state to showcase the grandeur of their colony to Europeans. Tourism allowed the colonial state to highlight infrastructural development and its role as a benevolent ruler.

Rijsttafel was an important apparatus for the colonial touristic venture. The interest in tourism led to the creation of the Official Tourists Bureau in 1908[25] initially based at the infamous Hotel des Indes[26], a non-profit institution subsidized by the colonial government.[27] A postcard from 1910 (Figure 4) depicts the Official Tourists Bureau promoting Java's historical and ecological features, such as "Famous Hindu ruins" and "30 active volcanoes," alongside technological advancements like "excellent railway and steamship" facilities, and notably, Western-standard accommodations, such as "Hotels with modern comfort." Another advertisement from the 1920s (Figure 5) describes a similar attitude toward tourism in the colony “In the course of centuries it has become one of the most highly developed of European colonies in Asia, and at the present time it is also drawing general attention as a most attractive tourist resort. The highly developed railway system in Java, and the splendid communication provided by the K.P.M. liners to the other islands of the Archipelago, as well as the excellent hotels in the various larger towns, enable the tourist to visit the most outlying districts of Netherlands India in comfort, and without any privation he has an opportunity to rub elbows with the various Oriental races that populate these enchanted isles.” The contrast between the colony's exotic allure and the availability of Western-standard accommodations shaped tourists' expectations in the Dutch East Indies. Similarly, the acceptance of Rijsttafel as a component of the colony's identity added to the exotic appeal for European tourists which was often served in modern establishments. Despite Rijsttafel being a highly anticipated component of the culinary adventure in the Dutch East Indies, efforts to restrict the consumption of colonial identities persist. The publication Het Indische Leven noted the strangeness of eating over-stimulating spice in the tropics served with ice-cold beer which would cause indigestion. Thus, the consumption of Rijsttafel should be limited to weekends only. Moreover, the publication suggests the importance of proper cuisine to make up for the lack of other pleasures in the colony.[28]

The popularity of Rijsttafel grew alongside the development of modern architecture in the Dutch East Indies. Rijsttafel served as a significant draw for numerous Western hotels as part of culinary tourism.[29] Unlike its portrayal in domestic settings, Rijsttafel represented abundance and luxury in the public sphere of the colony. Moreover, the abundance that Rijsttafel represented in the public realm also came with the array of native servants for each dish served (Figure 6). Well-known hotels throughout Java such as Hotel der Nederlanden and Hotel des Indes, advertised their cuisine as one of their selling points (Figure 7). While both hotels advertised their excellent cuisine, the imagery featured in the advertisements focused on the dining hall. The significance of the culinary experience extended beyond just the food to include the surrounding environment. The dining hall served as a crucial architectural element enhancing the experience for Western tourists. The familiarity of modern comfort and hygiene subdued colonial anxieties allowing European tourists to be Western in the colony. Thus, the demand for modern architecture increased as a result of tourism.

Simultaneously, a burgeoning architectural movement throughout 1907-1917 in the Netherlands spurred Dutch architects to explore opportunities in the Dutch East Indies. The Amsterdam School pursued a more artistically expressive architecture, while the more prevalent De Stijl movement favored rational and abstract design principles.[30] Despite lacking a firm theoretical or social foundation, the Amsterdam School prioritized the individual designer and unrestrained creative expression in its designs.[31] The appeal of unlimited space and freedom of expression attracted numerous Amsterdam School architects to the Dutch East Indies. However, the architectural style brought by the Amsterdam School to the Dutch East Indies often reflected cultural imperialism. Although not fully realized, the influence of the Amsterdam School was significant in shaping the development of the New Indies Style.[32]

The dining hall at Hotel Des Indes was one of the many examples of the development of the New Indies Style. Prominent architects from the New Indies movement worked on Hotel des Indes. One notable figure was P.A.J. Moojen. Moojen was the first independent architect who worked in a modern architecture style in the Dutch East Indies and many of his contemporaries considered him the first modern ‘Indische’ architect.[33] Prior to Moojen, architects practicing in the colony often imported European architecture while ignoring local cultures and climatic conditions. Moojen propelled the movement by maintaining the building methods of the Dutch East Indies while improving their architecture with Western influences. New Indies Style architecture can be characterized by the tropical climate adaptation of architectural movements seen in Europe at the time. Elements popular in the Art Deco movement such as white facades and horizontal articulation were commonly seen in New Indies Style. However, European elements such as flat roofs and tall buildings were uncommon due to climatic reasons and land availability.[34] Before the renovation, Hotel Des Indes embraced the colonial style with classical columns and arches. In 1906, P.A.J. Moojen assisted by S. Snuyf, renovated and brought modern influence such as the geometric decoration in the dining room.[35] The dining room at Hotel des Indes accommodated nearly 400 persons, connected to an extensive lounge.[36]

Part of the introduction of the modern architecture movement was the incorporation of modern technology. By 1913, the dining hall at Hotel des Indes had been equipped with electric fans and lamps. On the opposite side of the dining hall, the kitchen was furnished with large refrigerators, Western-style stoves, and baking apparatuses to prepare a variety of European dishes. Additionally, European machinery for kneading, washing, and polishing was also available. Hotel des Indes featured separate departments for pastry, bread baking, chicken and fish preparation, potatoes and vegetables, and Rijsttafel preparation (Figure 8).[37] Similarly, at Hotel der Nederlanden, the kitchen garnered praise for its extensive refrigeration rooms and European head chefs (Figure 9).[38] However, the native workers who prepared and served the dishes were often overlooked. Their roles were mainly in the background: in the kitchen, they functioned as another set of food preparation apparatus, while in the dining hall, they served as another fixture to complete the dining experience. The preparation, serving, and consumption of Rijsttafel juxtaposed European patrons with natives. Western architecture and technologies further accentuated the dichotomy between the served and the servants.

(Figure 8) Hotel des Indes kitchen showcasing European cooking equipments.

The introduction of imported European commodities such as architecture and food extended to the native population as part of the Dutch colonial mission to uplift and assimilate the colony. These imported European goods, seen as emblems of modernity, continued to gain popularity beyond domestic and touristic spaces. Recognizing the emergence of a native middle class as an opportunity, the Dutch colonial government sought to create a new market within the colony. Among numerous strategies, the establishment of fairs was one of the most significant tactics for introducing modernity. Unlike colonial fairs in the West, those in the colony served a distinct purpose. They aimed to promote the introduction of modernity and foster a vision of a united Dutch East Indies. The Gambir Fair in particular played a pivotal role in colonial propaganda. Before the Gambir Fair, other fairs in the colony already existed for industrial purposes. However, in the 1920s, Gambir Fair was reintroduced as a plan to integrate modern economic development.[39] Furthermore, the fair introduced modern culture such as leisure and entertainment through the consumption of modern products.[40] The Gambir Fair was unlike any other occasion in the colony before. Located at the heart of the urban fabric in Koningsplein (King’s Square), Batavia, the fair was open to everyone. It was monumental because it was a public space for every race supported by the Dutch government. For the first time, natives, Europeans, and other foreigners (Chinese and Arabs) celebrated the diversity of the colony. The objective of annual fairs such as the Gambir Fair was to civilize native populations through the consumption of Western culture[41], fostering a unified vision of the colony through modernity[42], and preparing them to be absorbed into the colonial empire.[43]

Modern architecture played a crucial role in realizing the Dutch colonial visions. Unlike the modern architecture at European standard hotels which was an adaptation of European architecture in the tropics, the architecture at Gambir Fair presented a novel blend of imported and local architecture. Elements of European architecture combined with native architecture including architecture from foreign Eastern cultures such as Chinese and Arab created a novel hybrid architecture (Figure 10). The architect of Hotel des Indes’s dining hall wrote in a Dutch newspaper for Batavia, D’Orient, regarding his astonishment at the architecture at Gambir Fair. Moojen wrote on the materiality and form of the pavilions at the fair. The structure of the fair combined silhouettes of traditional Indonesian architecture in a whimsical manner.[44] Moojen referred to the blend of architecture as Indonesian architecture instead of Dutch East Indies which signified a recognition of an identity separate from the Dutch empire and a unified vision of the colony. Later Moojen designed the Dutch East Indies pavilion at the Paris Colonial Exposition in 1931 inspired by the architecture of Gambir Fair (Figure 11). In addition, Gambir Fair celebrated modernity through modern technology such as electric lights (Figure 12).

The dichotomy between Dutch and native cultures was also evident through the juxtaposition of Dutch and native gastronomic culture. The practice of contrasting Dutch and native cultures proved to visualize not only a class and racial hierarchy but also what natives should desire. Native cuisine such as nasi goreng[45] existed alongside imported food brands such as Blue Band, Sun-Maid raisins, Coca-Cola, Victoria Biscuits and Heineken Beer.[46] Moreover, for an extra fare, rare Dutch cuisines such as pickled herring, rolmops, spekbokking, mackerel, mussels, Russian salad, Dutch cold cuts, kroket, and sausage rolls were available at exclusive restaurants.[47] The availability of imported goods did not mean they were within the financial and racial means of the native population. Additional fees and segregation were standard practices at the fair. Another aspect of food practices, hygiene, was also emphasized at the fair. Similar to hygiene propaganda for mothers in the domestic realm, the Dutch colonial government exhibited modern hygiene and sanitation practices that dealt with food preparation and other common diseases. For instance, at the Gambir Fair in 1930, a diorama illustrating the risks posed by flies around uncovered food at a warung[48] showcased typical unhygienic practices among natives (Figure 13).[49] Exposing and contrasting native and European cultures implied the primitiveness of the native population. Nonetheless, projecting modernity on the native population was important to the colonial mission of uplifting.

In the late colonial period of the Dutch East Indies, the intricate relationship between architecture and gastronomic culture serves as a lens through which we can understand the complexities of colonial power dynamics, identity formation, and the pursuit of modernity. Imported commodities, in the form of both architectural designs and culinary practices, were tangible expressions of the power dynamics at play within the colony, symbolizing the colonizers' assertion of modernity and superiority. At the domestic level, Dutch women were tasked with the responsibility of civilizing the colony by instilling European values and habits, including culinary preferences that mirrored those of the colonizers. The domestic sphere reflected the gendered dynamics of colonial power, as Dutch women navigated between their roles as housewives and agents of colonial assimilation. In touristic venues, such as hotels and restaurants, the juxtaposition of native cuisines like Rijsttafel with modern architectural designs showcased the dichotomy of native and European existence. Here, architecture and gastronomy converged to create an exotic allure for European tourists while reinforcing colonial hierarchies and cultural dominance. Furthermore, events like the Gambir Fair exemplified the colonial government's efforts to uplift the native population through the introduction of European culture and commodities. The complexities of power in the Dutch East Indies were manifested through the interplay of architecture and gastronomic culture, touching upon gender, race, and class dynamics within the colony. These imported commodities served as enduring reminders of the persistence of colonialism within the veneer of modernity.

*references availble upon request